The Chinese criminal justice system is complex and expansive. There are multiple forms of detention, multiple types of arrest, and countless opportunities for the authorities to delay and defer proceedings – as they have done with increasing frequency in recent years – before a case even makes it to trial.

This, of course, suits the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). A system that is difficult to navigate is easy to manipulate. It makes it harder for detainees, suspects, their lawyers and family members to know where they stand or even the charges they may be facing; it becomes more challenging for activists and journalists to report on and respond to crucial developments in a case, and ultimately nigh impossible for anyone the CCP is set on imprisoning to clear their name.

This blog aims to shed light on the key steps in the Chinese judicial process, and how they can be subverted as the authorities take advantage of vague language and myriad loopholes in the country’s Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) to prolong the suffering of those they have arbitrarily detained and imprisoned.

Detention

The process starts with detention, which is managed by what are known as public security organs. Article 85 of the CPL requires the authorities to notify a detainee’s family members within 24 hours of their detention, but even here there are exceptions, such as if ‘there is no way to contact them’, or where a detainee is accused of a ‘crime endangering national security’, or ‘terrorist activities’.

Of course, it is easy enough for the authorities to decide that a case involves national security, even when there is no evidence that it does. In December 2018, for example, police in Chengdu, Sichuan Province arrested Pastor Wang Yi of Early Rain Covenant Church – along with over 100 church members – on unfounded charges of ‘inciting subversion of state power’ after he spoke out on behalf of Christians and churches in the country and criticised controversial new regulations on religious affairs. He was sentenced to nine years in prison the following December.

Once an individual has been detained, a public security organ has three days to submit a request for arrest to the People’s Procuratorate (i.e. public prosecutor), however Article 91 of the CPL allows for this to be extended by one to four days under ‘special circumstances’, or even up to 30 days for ‘those suspected of committing crimes across multiple regions, committing multiple crimes, or cases of gang crimes’.

These criteria can be arbitrarily applied in many of the cases that CSW works on. For example, a pastor of an unregistered ‘house’ church is likely to lead a meeting the authorities deem illegal at least once a week; or a human rights defender may work on sensitive cases throughout an entire province or across the country; or a Falun Gong practitioner essentially commits a ‘crime’ in the eyes of the authorities every time that they practice a religion that has been banned in the country since 1999.

Before they are formally arrested, detainees are typically held in administrative detention centres, or Juliu Suo (literally ‘detain and stay facility’). These centres are managed by local public security departments, which are overseen by the Ministry of Public Security (MPS). Conditions vary widely within them as there are no public laws regarding their operation.

Arrest, Investigation and Prosecution

Once a public security organ has submitted a written request for the approval of an arrest, the People’s Procuratorate has seven days to respond. If the arrest is approved, the authorities once again have 24 hours to notify the suspect’s family members, though again exceptions can be made if ‘there is no way to inform them’ (Article 93, CPL). There is no clarity as to the criteria under which the authorities may decide this is the case.

Article 156 of the CPL stipulates that the authorities have two months to complete their investigation after an individual has been formally arrested, but this and subsequent articles in the CPL allow for multiple extensions totalling up to an additional five months with approval from the People’s Procuratorate. Specific circumstances in which investigations may be extended include in cases involving criminal gangs, ‘major, complicated cases of crimes being committed in several locations’, and even ‘major, complicated cases in remote regions where transportation is extremely inconvenient’ (Article 158, CPL). The law also enables the National People’s Congress to approve unspecified and theoretically indefinite extensions ‘when special circumstances make a particularly serious and complicated case unsuited for judgment for an extended period’ (Article 157, CPL).

Whilst under investigation, individuals are held in general detention centres, or Kanshou Suo (literally ‘watch and guard facility’). Much like administrative detention centres, conditions in these facilities vary widely. They are similarly administrated by local public security departments, but the perimeters are guarded by armed police. Individuals sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment with less than three months’ sentence remaining at the time of their sentencing are also held in these centres.

Particularly concerning is the fact that the authorities can essentially prolong this part of the process indefinitely by introducing or manufacturing new charges against an individual under investigation.

Article 160 of the CPL states that: ‘Where it is discovered during the investigation period that the suspect has committed other major offenses, follow article 156 of this law in restarting the period of investigatory detention from the date of discovery.’

This was the experience of Elder Zhang Chunlei of Love (Ren’ai) Reformed Church, who was detained in Guiyang, Guizhou Province in March 2021 after he visited a police station to enquire about a group of Christians who had been detained during a police raid on a private retreat. Zhang initially faced charges alongside three others of ‘illegally operating as an association’, but by the time he was formally arrested almost two weeks later the charge had been changed to ‘fraud’.

In January 2022, with Zhang having already spent over nine months in detention, it emerged that the authorities had also begun to investigate him for ‘inciting subversion of state power’, which they used to justify preventing him from seeing his lawyer, claiming that the case involved ‘state security’. Zhang was ultimately sentenced to five years in prison on 24 July 2024.

Even after an investigation has been concluded and a case has been transferred to the People’s Procuratorate for review, suspects can still wait months for a trial. The procuratorate has one month from this point to decide whether to initiate a prosecution, which can be extended by half a month in ‘major or complex cases’ (Article 172, CPL).

While examining a case, the procuratorate can also request two supplementary investigations, each of which can last up to one month and in turn resets the time the procuratorate has to decide whether or not to proceed with prosecution (Article 175, CPL).

Trial, Sentencing and Appeal

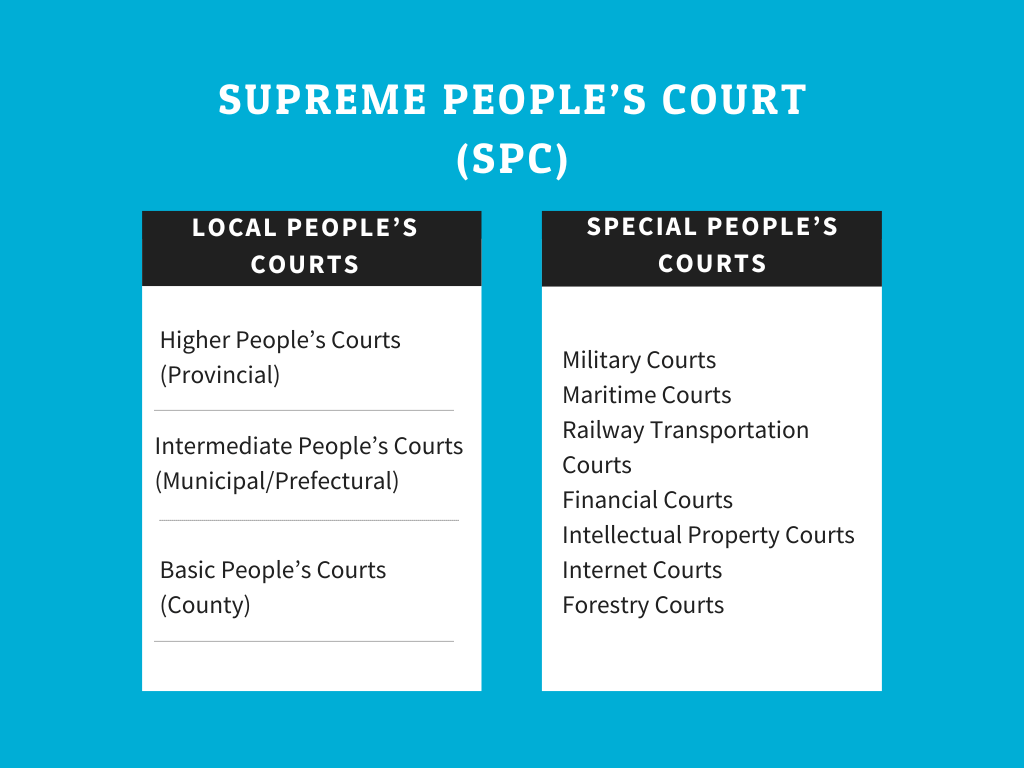

By the time an individual goes to trial they may have spent months or even years in various forms of detention, but trials themselves typically only last a single day. Sometimes these will be ‘show trials’, where the outcome is pre-scripted, and if the court decides at its discretion that the case involves ‘state secrets’ the trial will be conducted behind closed doors in accordance with Article 188 of the CPL.

Once a trial has concluded the court has three months to communicate its judgement (Article 208, CPL), which can be doubled to six with approval from a higher court for cases meeting the criteria laid out in Article 158 of the CPL. The period can also be further extended under ‘special circumstances’ with approval from the Supreme People’s Court, and the time limit is once again restarted if any supplementary investigations are conducted.

Appeals must be lodged at a court of the next higher level within ten days of a written judgement being issued, but even solid cases can fall on deaf ears if the authorities are determined to ignore them. Second-instance judgements are final, and must be communicated within four months of an appeal being accepted (Articles 243 & 244, CPL).

For example, Hui Muslim tour organiser Ma Yanhu was sentenced to eight years in prison on 21 June 2024 for ‘illegally crossing the border’ for his work to facilitate the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia for hundreds of Chinese Muslims a year. In his appeal letter, Ma and his lawyer laid out a clear case that the charges against him – which had been changed multiple times in the 15 months before his case proceeded to trial – violated the Chinese Constitution.

But this was not enough. Ma’s appeal was rejected on 19 August 2024. As he put it in his appeal letter, ‘If they decide someone is guilty, they must be guilty, regardless of the facts and the law.’

A prison sentence is not the end

Once an individual has been sentenced, they will be transferred to prison, where again conditions can vary widely but are generally better than those in detention centres. Most prisoners are able to make telephone calls or receive limited visits from close family members, and any time spent in detention from the point at which an individual has been formally arrested is discounted from their sentence.

But all this is of little consolation to those who have been unjustly and arbitrarily imprisoned, especially considering in some cases they will simply be re-arrested upon their release, or at the very least subjected to extensive surveillance and restrictions on their freedom of movement, expression, association and assembly.

There are also those who are subjected to even more secretive forms of detention – where human rights violations are more likely to occur and less likely to be investigated – such as Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL), in which an individual can be held incommunicado for up to six months in a police-designated location, or outright enforced disappearance such as that experienced by human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng since August 2017.

These practices must be abolished altogether, but it’s clear than even China’s standard criminal procedure requires urgent and significant reform. Vaguely defined terms and easily exploited loopholes must be removed from the CPL, and the CCP must ensure that cases are managed with greater transparency to ensure that due process and the fundamental right to a fair trial are upheld and respected.

This is not in the interests of a regime that routinely violates human rights and seeks to stifle any and all criticism of its leadership and policies, so it therefore falls to members of the international community that value justice, democracy and rule of law to increase their efforts to hold the CCP to account, and not to be intimated by its considerable economic and geopolitical might.

By CSW’s Press & Public Affairs Officer Ellis Heasley