On 20 August India’s Uttarakhand state government introduced significant amendments to its controversial anti-conversion law. Building on the original 2018 legislation and an initial round of amendments made in 2022, the Freedom of Religion and Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion (Amendment) Bill, 2025, imposes harsher punishments on a range of offences.

Individuals convicted of using allurement, misrepresentation or fraud to induce conversion now face anywhere from three to ten years in prison and a minimum fine of 50,000 rupees (approximately GBP £420). If the case involves a minor, a woman, a person with a disability, or a member of a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe, these penalties are increased to five to 14 years in prison and a fine of at least 100,000 rupees (GBP £840).

‘Mass conversions’ and those involving foreign funding are punishable with seven to 14 years imprisonment and a minimum fine of 100,000 rupees, while punishments for cases involving threats, assault, human trafficking, or marriage as a pretext for conversion can extend to 20 years or life imprisonment, along with fines covering the victim’s medical and rehabilitation costs.

The amendments also outline several new offences, including concealing one’s religion for the purposes of marriage, which is punishable by three to ten years in prison and a fine of 300,000 rupees (GBP £2,520), as well as committing any of the offences outlined in the bill through digital means.

Crucially, offences are now considered cognisable, which means that police are allowed to make arrests without warrants, and bail is granted only if the court is satisfied of the accused’s innocence and low risk of reoffending. Additional measures empower district magistrates to seize properties linked to conversion offences, placing the burden of proof on the accused to demonstrate legitimate ownership.

Discrimination justified

As is the case in the nine other Indian1 states in which so-called ‘freedom of religion’ laws are in force, Uttarakhand’s anti-conversion legislation has never really been about preventing coercive conversions as its proponents claim, and it is certainly not about upholding the fundamental right to freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) as the name might suggest.

In reality, these laws are vaguely worded, open to misuse, and discriminatory in their application. In many states they have been disproportionately enforced against religious minorities, to suppress interreligious relationships, and to restrict the free exercise of FoRB, which includes the right to choose or change’s one’s religion or belief as outlined in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which India has been a party since 1979.

Particularly concerning is the way in which these laws have also emboldened non-state actors – primarily right-wing Hindu nationalist groups – to interfere in individuals’ private decisions relating to their religion or belief, marriage and association, and in some cases even to violently attack those accused or suspected of involvement in forced conversions.

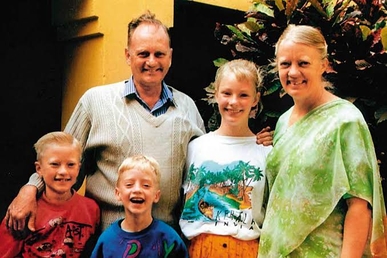

This connection has been clear in the country for decades. In January 1999 Australian Christian missionary Graham Staines and his two sons Philip, 10, and Timothy, 6, were burnt to death by Hindu extremists whilst they were sleeping in their car in Odisha State (then called Orissa), which was the first state in India to introduce anti-conversion legislation.

Staines had been falsely accused of forcibly converting Hindus to Christianity through his work with members of impoverished tribal communities and people with leprosy. Fourteen individuals were accused of involvement in the killings, however 12 were acquitted due to a lack of evidence. Dara Singh, the alleged mastermind behind the attack, remains imprisoned on a life sentence and continues to appeal for remission, while the only other convicted killer Mahendra Hembram was released in April this year after serving 25 years of a life sentence.

The Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), one of a group of Hindu nationalist organisations affiliated to the far-right Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) which also includes India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), described Hembram’s release as ‘a good day’.

An accelerating agenda

The recent amendments to Uttarakhand’s anti-conversion law, which place it among the most stringent in India, also highlight the alarming pace with which the anti-conversion agenda is taking hold across the country.

As mentioned, the amendments marked the second time the authorities have expanded the scope and severity of the law since it was introduced just seven years ago. It also bears emphasising that Uttarakhand is one of seven states to have implemented such laws since the BJP came to power in 2014, with two more – Arunachal Pradesh and Rajasthan – awaiting presidential assent for their own laws to come into effect.

Concurrently, the number of Christians to have been charged with conversion crimes in India has increased significantly,2 while provisions on interreligious marriages present in many of these laws have reinforced harmful communal narratives such as the ‘love jihad’ conspiracy theory that falsely claims that Muslim men marry Hindu women with the intention of converting them to Islam.

Meanwhile, authorities in these states, and indeed the federal government itself, continue to turn a blind eye to the real and highly concerning trend of the forcible conversion of religious minorities by Hindu nationalist groups under the guise of ‘ghar wapsi’, or ‘homecoming’ in Hindi.

Ghar wapsi is based on the fundamental belief that all Indians are originally Hindu, and therefore that converting ‘back’ to Hinduism signifies a return to one’s ancestry. Any and all conversions to Hinduism are considered ghar wapsi, and as such any forced conversions of religious minorities are not recognised or registered, despite multiple documented instances of exactly that.

In June this year, for example, members of the VHP and residents of the predominantly tribal village of Hirapur in Chhattisgarh state denied a Christian family access to the village cremation ground to cremate a relative. Five members of the family, including the deceased’s wife, were forced to perform the Hindu ritual of puja, to renounce the Bible by submerging it in a nearby river, and to drink Ganga Jal (holy water from the River Ganges) as a symbolic return to Hinduism before they were permitted to proceed with the cremation.

Intentions exposed

Ultimately the fact that the same authorities who appear wholly unconcerned by the trend of ghar wapsi – and in some cases actively celebrate and participate in it – are simultaneously introducing and strengthening laws ostensibly designed to prevent coercive conversions exposes their true intentions.

Their aim is to create an India in which to convert away from Hinduism, to celebrate one’s own religion, or even to post on social media can get you arrested or attacked, while to convert to Hinduism – even if under obvious duress – is considered a realisation of the true destiny of every Indian.

For a nation founded on the principles of democracy, diversity and equality, one with the fundamental human right to FoRB enshrined within constitution, this is a tragedy. The international community should remind the government of India of these principles, holding Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the BJP and the extremist voices with whom they continue to trample all over them to account.

By CSW’s Press & Public Affairs Officer Ellis Heasley

- In addition to Uttarakhand, anti-conversion laws are currently in force in Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh. ↩︎

- According to the United Christian Forum (UCF), a helpline service for persecuted Christians in India, 238 Christians were charged with conversion crimes in 2024, compared to 57 in 2021. ↩︎