As Nepal prepares to head to the polls on 5 March, the nation finds itself at a profound crossroads. This general election follows a period of significant political upheaval, including the youth-led protests of 2025 that led to the dissolution of the previous government and the appointment of an interim cabinet. For the approximately 18.9 million registered voters, the stakes extend far beyond economic stability or infrastructure; they touch upon the very identity of the nation.

The following Q&A conducted with Pastor Tanka Subedi, a human rights defender and entrepreneur based in Kathmandu, explores the intricate intersection of religion or belief and politics, examining how the upcoming vote might reshape every Nepali’s right to freedom of religion or belief (FoRB).

For readers outside Nepal, how would you describe the country’s religious mix today?

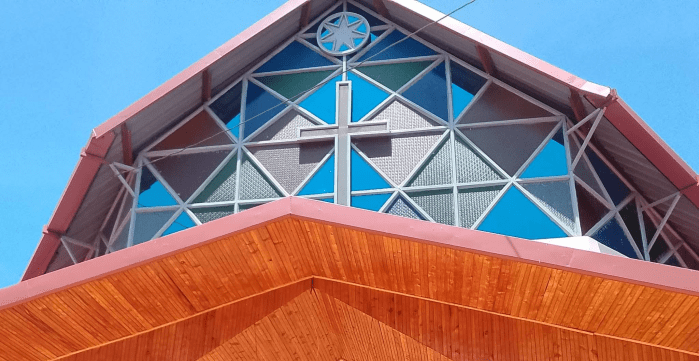

In general, people in Nepal coexist relatively peacefully with followers of other religions, provided that members of their own family or close community are not perceived to be converting. Tensions may arise when organised groups or individuals mobilise sentiment against another religion. Many Hindus consider Buddhists, Kirat, and Masto traditions as part of the broader Hindu cultural framework, and adherents of these traditions often accept this understanding. Islam is largely tolerated within society. Christianity, however, is frequently perceived as a foreign religion, which contributes to social suspicion and sensitivity around its growth.

Continue reading “What’s at stake in Nepal’s general election: An interview with a pastor and human rights defender”